CHIARI MALFORMATIONS (PRONOUNCED: KEE-AH-REE) ARE STRUCTURAL DEFECTS IN WHICH THE CEREBELLUM, THE HIND PART OF THE BRAIN, DESCENDS BELOW THE FORAMEN MAGNUM INTO THE SPINAL CANAL.

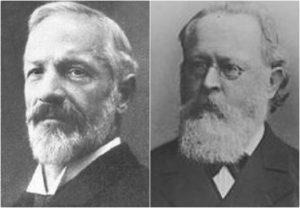

While Arnold Chiari Malformation (Type 2) was first identified in the late 19th century by the Austrian pathologist Hans Chiari, much of the current medical knowledge has developed since 1985 with the expanded use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). The number of patients diagnosed with Chiari malformations continues to increase, and with that increase Chiari Malformation is getting some of the attention the condition has always demanded.

Chiari malformations (“CMs”) are neurological disorders in which the cerebellum extends out of the skull and into the spinal canal, which in turn blocks the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, puts pressure on the brainstem and spine, and may result in varying degrees of nerve compression. Once thought to occur in 1 in 1000 people, it is now believed to be much more frequent of an occurrence. A 2016 pediatric study found it to occur in 1 in 100 children[1]. However, since the most common type (Type 1) tends to become symptomatic during late teens and early adulthood, it is likely to be much more common when adults are factored in. Females are more likely than males to have a Chiari Malformation (at a ratio of 3:1), and significantly higher amongst those with both Chiari Malformation and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (9:1)[2]. We affectionately refer to those that live with this condition, including the attendant pain and frequent disregard from the medical community, as Chiarians (regardless of whether they have had surgical intervention or not).

While some Chiarians are symptomatic throughout their lifetime, the vast majority of Chiarians (those with Type 1) develop symptoms in their late teens or early adulthood. Those symptoms can range from mild to crippling, and can become severe enough to cause paralysis (often associated with syringomyelia) or death.

WHAT CAUSES A CHIARI MALFORMATION?

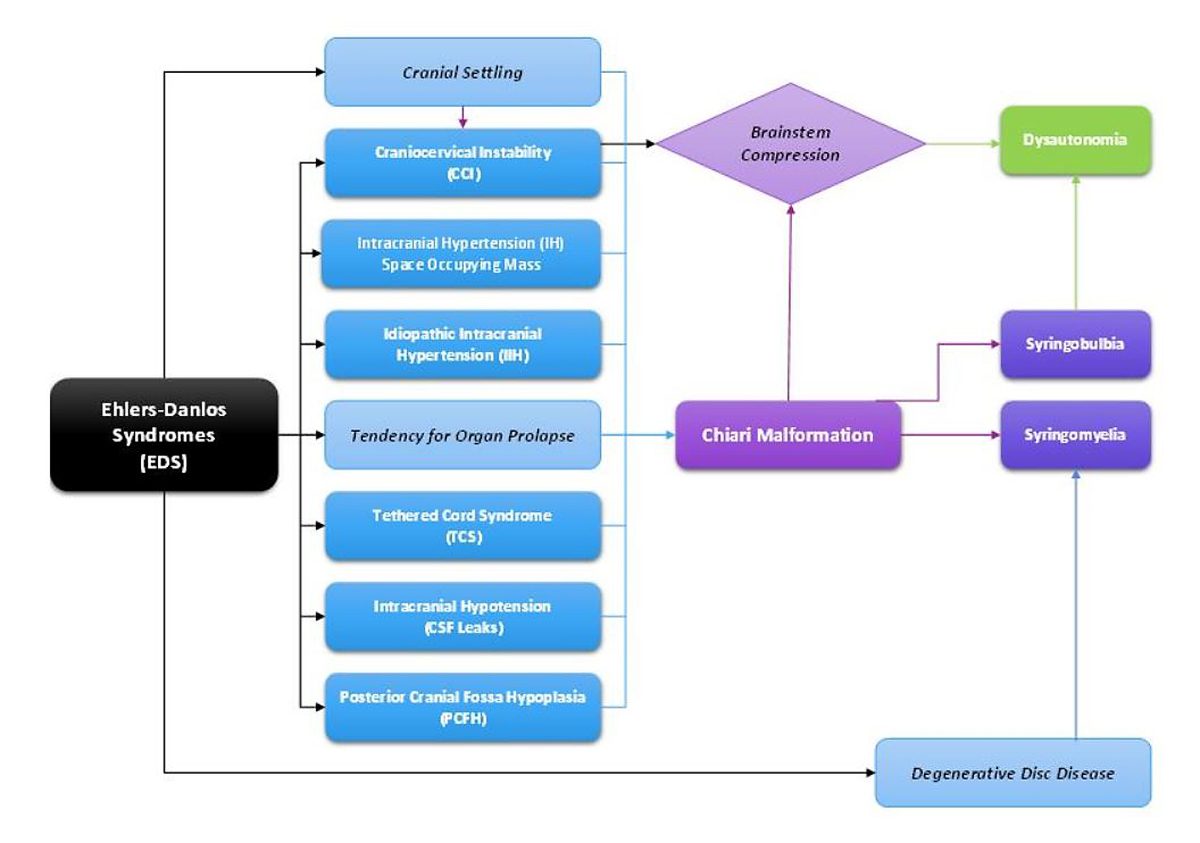

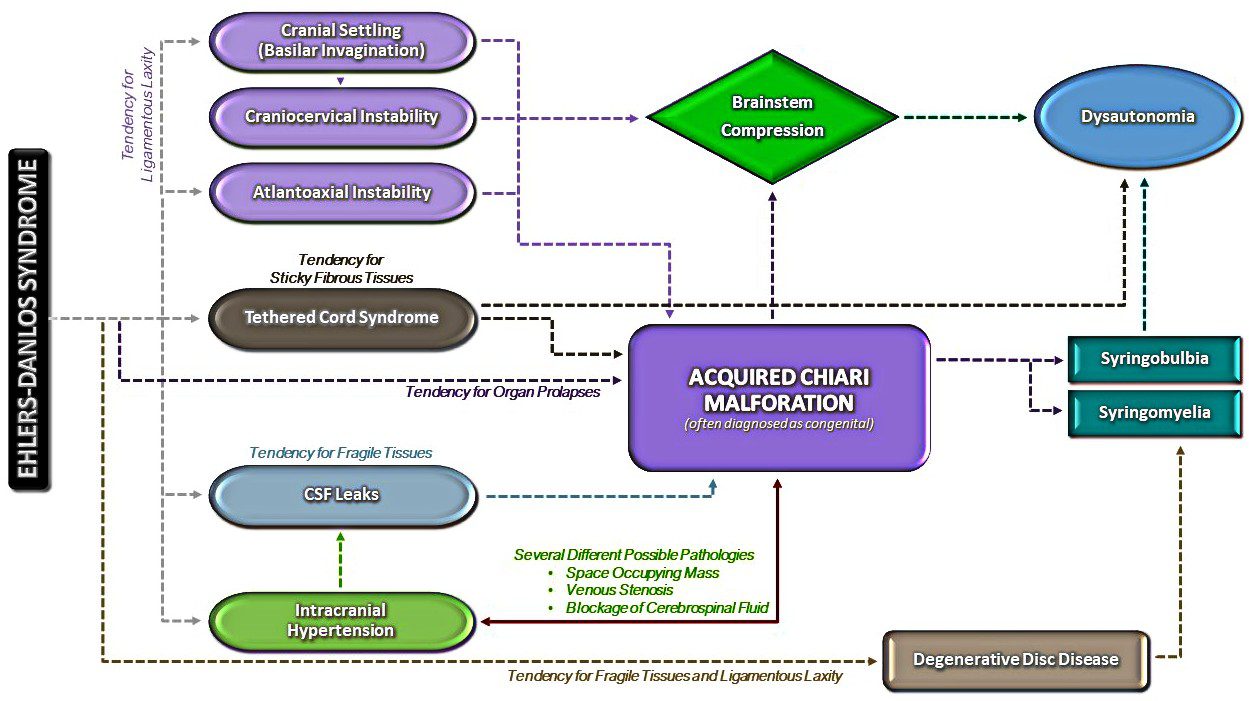

Multiple factors have been identified which can either cause or attribute to Chiari malformations. Although they too were once thought to be rare, Acquired Chiari malformations are now being diagnosed in increasing numbers. A brief overview of what each of these labels entail, together with a summary of the different types of CM’s, is provided below:

- Congenital Chiari, is believed to be caused by a posterior cranial fossa hypoplasia (PCFH)[3], which can also be caused by a connective tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos.[4] While the cerebellum continued to grow in utero, the posterior skull failed to grow proportionately. Problems resulting from this size discrepancy continue and eventually the overcrowding of the hindbrain squeezes the cerebral tonsils downward into the opening of the spinal canal (cranial constriction). While the herniation of the cerebellar tonsil(s) can take place during gestation or after birth, because the cause is 100% congenital, and the process most likely began in utero, it is usually considered a Congenital Chiari Malformation when the only pathology found is a small posterior cranial fossa. In one large study, they found those with a Chiari Malformation and no associated etiological/pathological co-factors, with only slightly over 52% having a small PCF. When other co-factors were present, the number of Chiarians found with a small PCF plummeted, and therefore it should be considered acquired until proven otherwise.[5]

- Acquired Chiari can have one or more possible pathological co-factors; any of which can result in the descent of the cerebellar tonsils. Many Chiarians often mistakenly conceptualize an Acquired Chiari Malformation as being brought on only by trauma; however, “acquired” is an antonym for “congenital,” so an Acquired Chiari Malformation in medical terms is one that a person was not born with. While this can include Acquired Chiari malformations resulting from trauma, it can also include Acquired Chiari malformations resulting from a variety of other medical conditions:

Special care should be taken when any of these co-morbid conditions exist in conjunction with a Chiari Malformation. Before the consideration of decompression surgery, a plan should be developed which addresses each possible comorbid condition before decompression. This can reduce the likelihood of complications and/or a failed decompression surgery.

SEVEN TYPES OF CHIARI MALFORMATIONS WORTH DISCUSSING (asterisks “*” indicate commonly known types)

Chiari Zero: The lower part of the cerebellum (the cerebral tonsils) are blocking the foramen magnum, but are not descended through. Because of the cerebellum’s position, it blocks the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and all the effects of that blockage are comparable to Type 1.

Diagnosis Requirements: Symptomology; MRI showing no herniation but the low-lying tonsils that are pressing against the top of the foramen magnum; MRI showing a syrinx (despite the name, Chiari Zero is classified under Syringomyelia and not Chiari Malformation – so a syrinx is technically required for diagnoses). [6][7]

Treatment Options: With few symptoms, non-surgical treatments might be recommended. When a syrinx is present, a decompression is often recommended before the syrinx has a chance to further develop and cause additional damage to the spine. However, even when a syrinx is present, all pathological cofactors should be explored and addressed prior to decompression surgery.

Chiari 0.5: In cases of Chiari 0.5, the lower part of the cerebellum (the cerebral tonsils) are descended through the foramen magnum, but descends < 5mm (which is the measurement that some doctors use to define Chiari). Usually labeled “tonsillar ectopia” on radiology reports, the symptoms and effects of the obstruction are generally the same as those experienced with Type 1 or Chiari 1.5.[3]

Diagnosis Requirements: Symptomology; MRI showing a herniation of < 5mm, unless already properly diagnosed with a Type 1 or Chiari 1.5; presence of a syrinx is not “required” for diagnosis, but as with Chiari Zero, it illustrates that it is causing a problem obstructing the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and may be relevant when deciding between various courses of treatment.

Treatment Options: The same as Type 1 or Chiari 1.5, respectively.

*Chiari Malformation Type 1: The most common type of Chiari Malformation, Type 1 is diagnosed when the cerebral tonsils descend below the foramen magnum. Medical professionals unfamiliar with current research surrounding Chiari Zero and Chiari 0.5 (and the symptomology surrounding the blockage of cerebrospinal fluid), believe that a tonsillar herniation of less than 5mm is simply a tonsillar ectopia and only diagnose a Chiari Malformation when the descent is > 5mm. However, the 5mm requirement is controversial, and many doctors now base their diagnoses not solely on measurements, but rather on symptomology and a combination of other factors, including cine MRI’s, a patient’s symptoms, and other relevant factors.[6] Many people with a Chiari Zero, Chiari 0.5, or Type 1 can be asymptomatic for a lifetime: one large study found that approximately 30% of those with a CM measuring between 5-10mm were asymptomatic.[8] If symptoms develop, they often present in adolescence or early adulthood. Anecdotal evidence supports the proposition that once symptoms start, the symptoms often progress rapidly until the damage is stopped surgically.

Diagnosis Requirements: Symptomology; MRI indicating at least one herniated tonsil (without the brainstem descending as well).[9]

Treatment Options: Prior to surgery any/all comorbidities should be explored and treated especially if you are found to have a normal sized posterior fossa. However, if you have classic Chiari 1 Malformation with a small posterior fossa, the risks of surgery should be weighed against the severity of symptoms and the impact that symptoms are having on the patient’s quality of life. It is often recommended to treat mild symptoms with medication, with surgical options typically reserved for cases in which symptoms cause more serious medical and quality of life problems. However, symptoms do tend to progress, and studies have shown a correlation between successful decompression surgery and the amount of time between the onset of any symptoms and surgical intervention[10]. See “Decompression Surgery” below.

Chiari 1.5: This type of CM (often referred to as a “Complex Chiari”) is often acquired as opposed to congenital. Chiari 1.5 should be the diagnosis when the tonsil(s) and all/part of the lower brainstem (the medulla oblongata) has descended past the foramen magnum. This is usually indicative of another comorbid condition pushing the brainstem downward from above or pulling downward from below.[5][11][12]

Diagnosis Requirements: symptomology; MRI indicating at least one herniated tonsil AND a downward displacement of all/part of the brainstem; without the other radiological findings associated with Type 2.

Treatment Options: Treatment options can vary significantly from patient to patient depending on the cause of the Chiari 1.5. While a variety of medical options might initially be used to treat symptoms, it is extremely important that all possible causes and/or comorbidities are thoroughly investigated and treated prior to the consideration of decompression surgery. Failure to identify and treat any such conditions can increase the likelihood of a failed decompression and further complications such as brain slumping, increased cervical instability, etc.

*Chiari Malformation Type 2 (also known as Arnold Chiari Malformation): Type 2 involves a herniation of the cerebellar tonsils and lower part of the brainstem (the medulla oblongata). Unlike in Chiari 1.5, in Type 2 the fourth ventricle is usually herniated, all/part of the cerebellar vermis (the tissue connecting both halves of the cerebellum) is missing or herniated, the corpus callosum (nerve fibers connecting both hemispheres of the brain) is fully/partially absent (agenesis), and it is almost always accompanied by a myelomeningocele (the most serious form of Spina Bifida, a congenital neural tube defect where the spinal canal does not close properly).[13][14][15]

Diagnosis Requirements: While a myelomeningocele is usually evident and diagnosed at birth, a brain MRI should confirm the radiological aspects of Type 2.

Treatment Options: Myelomeningocele is usually treated surgically at birth. If other related problems develop, such as hydrocephalus and/or tethered cord, they are often dealt with surgically as they become problematic. While some with Type 2 are decompressed, anecdotal evidence reflects a general trend of an increased failure rate with decompression surgeries as compared to those with Type 1. Because of this, some neurosurgeons choose not to decompress those with Type 2.

*Chiari Malformation Type 3: Type 3 is a serious type of Chiari Malformation involving herniated cerebellar tonsils, brainstem, and fourth ventricle. However, in most cases of Type 3, a sac forms out of the back of the skull (encephalocele) that contains brain matter from the cerebellum and the meninges. Type 3 causes severe neurological problems that are evident at birth and has a high infant mortality rate.[16][17]

*Chiari Malformation Type 4: Type 4 is the most severe type of Chiari Malformation, but does not involve a hindbrain herniation (and therefore arguments have been made that it is not a Chiari Malformation). Instead, it consists of an undeveloped or underdeveloped cerebellum. Most infants born with Type 4 die in infancy.[16][17]

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Decompression surgery is currently the only available means of attempting to stop the progression of symptoms of a congenital chiari (with no other pathological cofactors), but decompression is not a cure (not even close). Statistics show that up to 69% of decompressed patients find some measure of relief from surgery (usually headaches)[18]. Most neurosurgeons will give only a 50% chance of helping each individual symptom. Some of the symptoms are irreversible once they develop. Recent studies show that there is a correlation between early surgical intervention and positive post-surgical outcomes.[19] However, we cannot over emphasize the importance of your doctors taking time to find, diagnose, and treat co-morbid conditions BEFORE decompression surgery. If they are not willing to consider comorbidities, they are probably not the doctor for you!

[wpedon id=”4396″ align=”center”]

*Original version released January 2018, revised October 2018.

References:

1 Eltorai, Ibrahim M. “Rare Diseases and Syndromes of the Spinal Cord” Cham: Springer International Publishing: Imprint: Springer, 2016. Page 43, 15.2, <www.springer.com/us/book/9783319451466>.

2 Henderson, Fraser C., et al. “Neurological and Spinal Manifestations of the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes.” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 21 Feb. 2017, <www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajmg.c.31549/full>.

3 Sekula, Raymond F, et al. “Dimensions of the Posterior Fossa in Patients Symptomatic for Chiari I Malformation but without Cerebellar Tonsillar Descent.” Cerebrospinal Fluid Research, BioMed Central, 2005, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1343586>.

4 Stagi, Stefano, et al. “The Ever-Expanding Conundrum of Primary Osteoporosis: Aetiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics, BioMed Central, 2014, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4064514>.

5 Milhorat, Thomas H., et al. “Mechanisms of Cerebellar Tonsil Herniation in Patients with Chiari Malformations as Guide to Clinical Management.” Acta Neurochirurgica, Springer Vienna, July 2010, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2887504>.

6 Isik, N, et al. “A New Entity: Chiari Zero Malformation and Its Surgical Method.” Turkish Neurosurgery., U.S. National Library of Medicine, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21534216>.

7 “JNS JOURNAL OF Neurosurgery OFFICIAL JOURNALS OF THE AANS since 1944.” The Resolution of Syringohydromyelia without Hindbrain Herniation after Posterior Fossa Decompression | Journal of Neurosurgery, Vol 89, No 2, <www.thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/jns.1998.89.2.0212?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed>.

8 Elster, A D, and M Y Chen. “Chiari I Malformations: Clinical and Radiologic Reappraisal.”Radiology., U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 1992, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1561334>.

9 Wilson, Eugene. “Chiari.” CEDSA Home, <www.cedsa.org/index.php/59-quick-reference/73-chiari.html>.

10 Hindawi. “Surgical Management of Patients with Chiari I Malformation.” International Journal of Pediatrics, Hindawi, 28 June 2012, <www.hindawi.com/journals/ijpedi/2012/640127>.

11 Kim, In-Kyeong, et al. “Chiari 1.5 Malformation : An Advanced Form of Chiari I Malformation.”Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, The Korean Neurosurgical Society, Oct. 2010, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2982921>.

12 Malik, Amita, et al. Chiari 1.5: A Lesser Known Entity. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, <www.annalsofian.org/article.asp?issn=0972-2327;year=2015;volume=18;issue=4;spage=449;epage=450;aulast=Malik>.

13 Wolpert, Samuel M, et al. “Chiari II Malformation: MR Imaging.” American Journal of Roentgenology, <www.ajronline.org/doi/pdf/10.2214/ajr.149.5.1033>.

14 Yumer, M H, et al. “Chiari Type II Malformation: a Case Report and Review of Literature.”Folia Medica., U.S. National Library of Medicine, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16918056>.

15 Kim, Irene. “Chiari II Decompression in Patients with Myelomeningocele in the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry (NSBPR).” <http://spinabifidaassociation.org/sbworldcongress/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2017/04/B.4-Kim-Neurosurgery.pdf>.

16 “Chiari Malformation Fact Sheet.” National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, <www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Chiari-Malformation-Fact-Sheet>.

17 “Chiari Malformations.” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), <www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/chiari-malformations>.

18 14 Aliaga, L, et al. “A Novel Scoring System for Assessing Chiari Malformation Type I Treatment Outcomes.” Neurosurgery., U.S. National Library of Medicine, Mar. 2012, <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21849925>.

19 Siasios, John, et al. “Surgical Management of Patients with Chiari I Malformation” International Journal of Pediatrics, Article ID 640127, Hindawi, 2012, <www.hindawi.com/journals/ijpedi/2012/640127>.

Palliative Care (pronounced “pal-lee-uh-tiv” care) is a subspecialty of medical care, where an interdisciplinary team of professionals (both medical and social) are committed to helping provide “relief from symptoms and stress” for patients with serious, life-altering illnesses, and their families.

Palliative Care (pronounced “pal-lee-uh-tiv” care) is a subspecialty of medical care, where an interdisciplinary team of professionals (both medical and social) are committed to helping provide “relief from symptoms and stress” for patients with serious, life-altering illnesses, and their families.  Misconceptions Surrounding Palliative Care:

Misconceptions Surrounding Palliative Care:  Primary Care Doctors (who are supposed to be offering referrals to Palliative Care for their patients with serious medical conditions) often fail to fully understand the spectrum of Palliative Care. Because of their faulty understanding, most of us are never offered Palliative Care, and when we request it, we are often told that it is equivalent to hospice care or set aside for hospice patients, and therefore they believe that we do not qualify. THEY ARE WRONG!

Primary Care Doctors (who are supposed to be offering referrals to Palliative Care for their patients with serious medical conditions) often fail to fully understand the spectrum of Palliative Care. Because of their faulty understanding, most of us are never offered Palliative Care, and when we request it, we are often told that it is equivalent to hospice care or set aside for hospice patients, and therefore they believe that we do not qualify. THEY ARE WRONG!

![Overview: Chiari Malformation [Revised]](https://chiaribridges.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Fotolia_79774600_XS.jpg)

But to look at the full history of what became known as a Chiari Malformation, we can begin by looking at the research of a German

But to look at the full history of what became known as a Chiari Malformation, we can begin by looking at the research of a German  Unfortunately it leaves most of us with failed decompressions, fighting with our neurosurgeons that “something is still wrong.” These neurosurgeons look at their post-operative checklist and see that they successfully did everything surgically required in their out-of-date textbooks:

Unfortunately it leaves most of us with failed decompressions, fighting with our neurosurgeons that “something is still wrong.” These neurosurgeons look at their post-operative checklist and see that they successfully did everything surgically required in their out-of-date textbooks:

Empowering With Knowledge!

Empowering With Knowledge!  be, but if we continue to see all that we can do and not just what we cannot do, we can dare to dream again! We are all multifaceted human beings with broad gifts and talents. We might not be the athletes we once aspired to be, but that says nothing of our strength. We all have the potential to change the world around us! You might be an artist that hasn’t practiced your art in years – start practicing again! You might have always thought about writing books, but because of your diminished hope for the future, you haven’t written in years – pick up a pen and start writing again! The only way to ever know your true potential is to try and try again! Dare to dream again!

be, but if we continue to see all that we can do and not just what we cannot do, we can dare to dream again! We are all multifaceted human beings with broad gifts and talents. We might not be the athletes we once aspired to be, but that says nothing of our strength. We all have the potential to change the world around us! You might be an artist that hasn’t practiced your art in years – start practicing again! You might have always thought about writing books, but because of your diminished hope for the future, you haven’t written in years – pick up a pen and start writing again! The only way to ever know your true potential is to try and try again! Dare to dream again!

Pain from a Chiari headache can be brought on from the simplest of things – a sneeze, a cough, laughter, or bearing down when going to the bathroom. We never know when the headache is going to strike, how long it will last, or when it will end. We are unable to describe the intensity of the pain to others, and when asked to rate our pain on a scale of 1 – 10, we want to scream, “14!” The radiating, crushing pain of the headaches robs us of our ability to function for days on end. And depending on the extent of damage the Chiari has caused you may also have the burning, stabbing, and shooting involved with

Pain from a Chiari headache can be brought on from the simplest of things – a sneeze, a cough, laughter, or bearing down when going to the bathroom. We never know when the headache is going to strike, how long it will last, or when it will end. We are unable to describe the intensity of the pain to others, and when asked to rate our pain on a scale of 1 – 10, we want to scream, “14!” The radiating, crushing pain of the headaches robs us of our ability to function for days on end. And depending on the extent of damage the Chiari has caused you may also have the burning, stabbing, and shooting involved with  By a wide margin, the hardest part of our fight is dealing with doctors. One would think it would be the never-ending pain, but when your doctors do not believe you, ridicule you, or outright verbally abuse you, it not only adds insult to injury, but it probably illustrates reasons that your doctor(s) just might be the ones that need counseling. As patients, we are paying for them to help us with our medical problems; what we get instead is usually a referral to a therapist because of their ineptitude. The absurd part of this circle of insanity is that when we make ourselves more knowledgeable about our condition(s), because we have no other choice, a doctor that understand the Hippocratic Oath would respond by making themselves more knowledgeable as well, so they can help their patients. Yet, what is far too common are doctors that do not want to know the results of studies, who are complacent with their fifteen minutes of Chiari education, and think if they talk a good game, patients can be manipulated into thinking maybe it’s all in their minds.

By a wide margin, the hardest part of our fight is dealing with doctors. One would think it would be the never-ending pain, but when your doctors do not believe you, ridicule you, or outright verbally abuse you, it not only adds insult to injury, but it probably illustrates reasons that your doctor(s) just might be the ones that need counseling. As patients, we are paying for them to help us with our medical problems; what we get instead is usually a referral to a therapist because of their ineptitude. The absurd part of this circle of insanity is that when we make ourselves more knowledgeable about our condition(s), because we have no other choice, a doctor that understand the Hippocratic Oath would respond by making themselves more knowledgeable as well, so they can help their patients. Yet, what is far too common are doctors that do not want to know the results of studies, who are complacent with their fifteen minutes of Chiari education, and think if they talk a good game, patients can be manipulated into thinking maybe it’s all in their minds. In a distant second, would have to be the heart-wrenching feeling we get when our loved ones put more stock in the opinions of our morally bankrupt doctors, even once we have shared study after study and article after article showing you that our doctors are wrong. What we go through, feeling like our bodies have betrayed us, knowing that our doctors have betrayed us (even if it is because they do not know any better), we need you in our corner. This is the fight of our lives, for our lives, and we should never have to do it alone! The energetic, feisty, loving person that you have loved so much over the years is still inside of us! When your brain falls into your

In a distant second, would have to be the heart-wrenching feeling we get when our loved ones put more stock in the opinions of our morally bankrupt doctors, even once we have shared study after study and article after article showing you that our doctors are wrong. What we go through, feeling like our bodies have betrayed us, knowing that our doctors have betrayed us (even if it is because they do not know any better), we need you in our corner. This is the fight of our lives, for our lives, and we should never have to do it alone! The energetic, feisty, loving person that you have loved so much over the years is still inside of us! When your brain falls into your  (apparently, they do not know the importance of the

(apparently, they do not know the importance of the