Pronounced, kee-AH-ree mal-for-MAY-shun.

Whether you are new to Chiari or wondering why you are still experiencing debilitating symptoms after decompression, this is a good place to start.

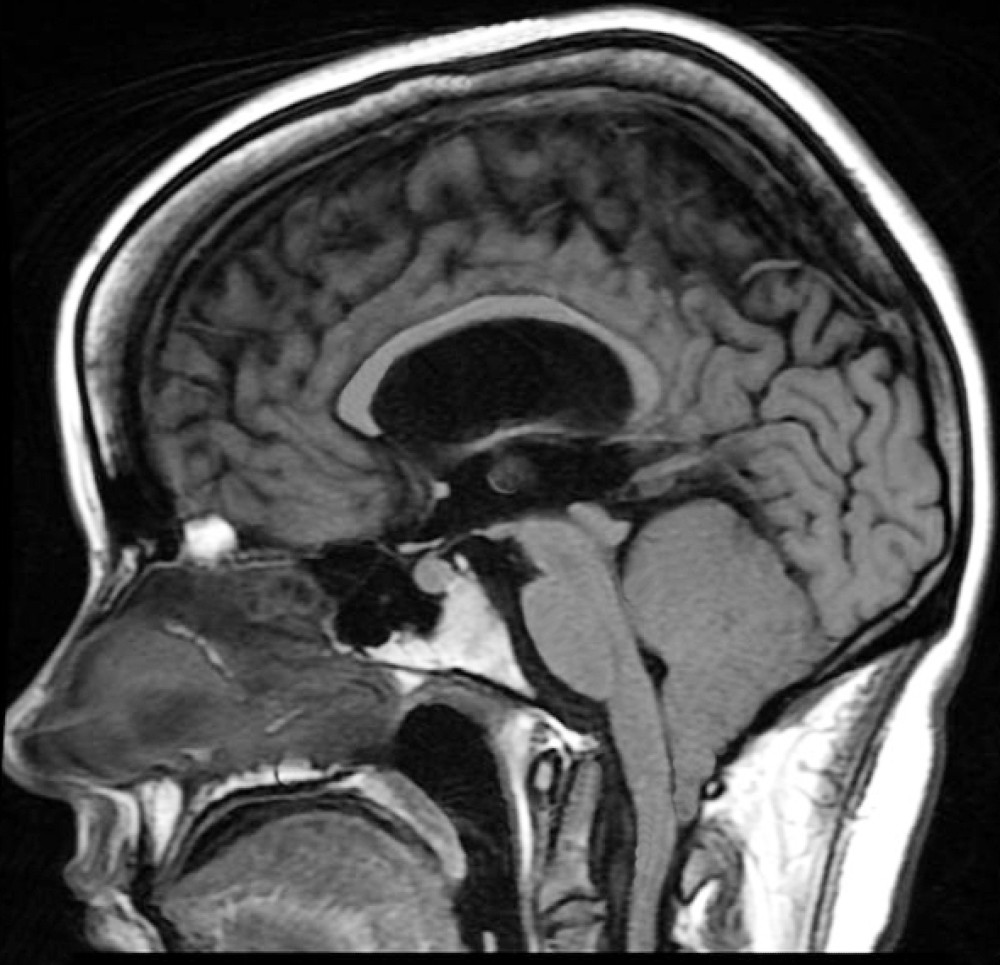

While our site concentrates on Chiari Zero, Chiari 1, Chiari 1.5, and touches on Chiari 2, all of them involve one or more problems with the cerebellum (Latin for "little brain"). The cerebellum is the largest structure of the hindbrain. It accounts for about 10% of the brain’s total volume, yet it contains over 50% of all the brain’s neurons.[1]

Multiple factors have been identified which can either cause or attribute to Chiari malformations.[2] Although they too were once thought to be rare, Acquired Chiari malformations are now being diagnosed in increasing numbers. A brief overview of what each of these labels entail, together with a summary of the different types of CM’s, is provided below:

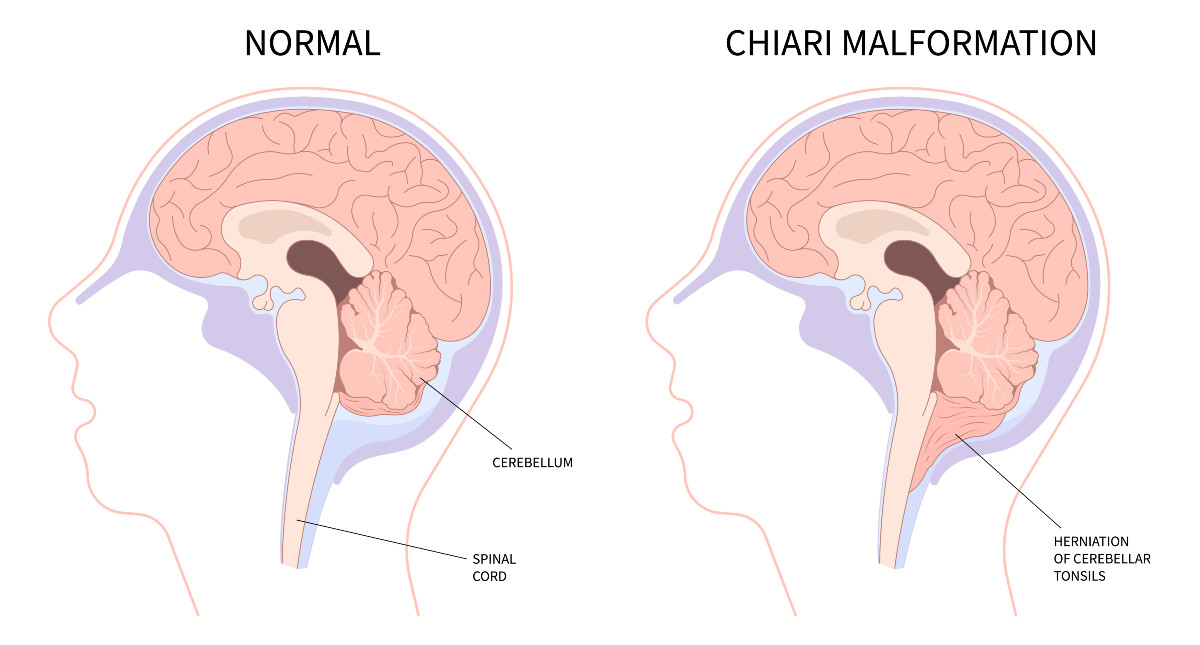

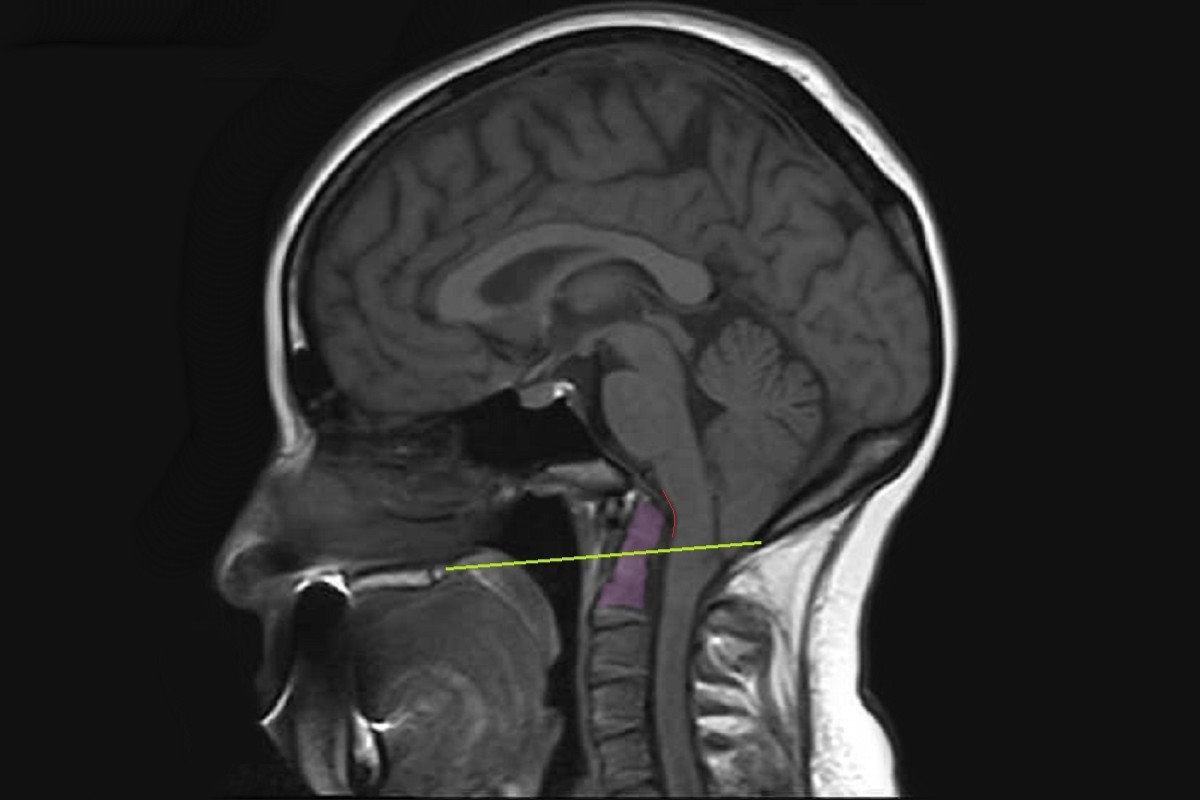

Congenital Chiari is believed to be caused by a posterior cranial fossa hypoplasia (PCFH).[3] While the cerebellum continued to grow in utero, the posterior skull failed to grow proportionately. Problems resulting from this size discrepancy continue and eventually the overcrowding of the hind-brain squeezes the cerebral tonsils downward into the opening of the spinal canal (cranial constriction). While the herniation of the cerebellar tonsil(s) can take place during gestation or after birth, because the cause is 100% congenital, and the process most likely began in utero, it is usually considered a Congenital Chiari Malformation when the only pathology found is a small posterior cranial fossa. In one large study, they found those with a Chiari Malformation and no associated etiological/pathological co-factors, with only slightly over 52% having a small PCF. When other co-factors were present, the number of patients found with a small PCF plummeted, and therefore it should be considered acquired until proven otherwise.[4]

Acquired Chiari can have one or more possible pathological co-factors; any of which can result in the descent of the cerebellar tonsils. Many patients mistakenly conceptualize an Acquired Chiari Malformation as being brought on only by trauma; however, “acquired” is an antonym for “congenital,” so an Acquired Chiari Malformation in medical terms is one that a person was not born with. While this can include Acquired Chiari malformations resulting from trauma, it usually refers to herniated tonsils secondary to a variety of other medical conditions:[2]

Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue (HDCTs), most commonly Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS), make the tonsils more prone to prolapse below the foramen magnum.

Multiple conditions are known to create a pushing/pulling effect that can result in a tonsillar herniation. These conditions include: Intracranial Hypertension (IH), Atlantoaxial Instability and Craniocervical Instability (AAI/CCI), Tethered Cord Syndrome (TCS), and Intracranial Hypotension (cerebrospinal fluid leaks), Hydrocephalus, and a variety of cysts and brain tumors.[5]

Special care should be taken when any of these co-morbid conditions exist in conjunction with a Chiari Malformation. Before the consideration of decompression surgery, a plan should be developed which addresses each possible comorbid condition before decompression. This can reduce the likelihood of complications and/or a failed decompression surgery.

The lower part of the cerebellum (the cerebral tonsils) are blocking the foramen magnum, but are not descended through. Because of the cerebellum’s position, it blocks the flow of cerebrospinal...

[Read More]

The most commonly diagnosed type of Chiari Malformation, Type 1 is diagnosed when the cerebral tonsils descend below the foramen magnum, but the brainstem does not. The cerebellar tonsils...

[Read More]

Chiari Malformation, Type 1.5 is rarely recognized, but should be diagnosed when the cerebral tonsils AND THE BRAINSTEM descend below the foramen magnum...

[Read More]

Also known as Arnold Chiari Malformation: Type 2 involves a herniation of the cerebellar tonsils, a herniated medulla, the fourth ventricle is usually herniated, a missing or herniated...

[Read More]

A small posterior fossa does not cause a problem unless it pushes the cerebellar tonsils down into the foramen magnum (the hole at the base of the skull), causing a blockage of cerebrospinal fluid. Yet, the size of that herniation is THE ONLY THING that doctors routinely measure when they diagnose a Chiari Malformation. They diagnose according to a criteria that only considers the size and appearance of the cerebellar tonsils (without measuring the posterior cranial fossa at all).

✅ Are the cerebellar tonsils herniated by at least 3-5mm?

✅ Are the cerebellar tonsils pointy enough?

While a small posterior fossa can cause the cerebellar tonsils to prolapse, there are many conditions that can also cause the tonsils to herniate. When these pathological (causal/attributing) factors go untreated and are allowed to continue pushing/pulling the cerebellar tonsils downward, the brain fails to become buoyant and the patient is left with an even larger hole for the brain to slump into, once again restricting the flow of cerebrospinal fluid. While the patient may initially get a measure of relief from the decompression allowing the CSF to flow, once the brain drops into the hole, the symptoms resume, and doctors are less likely to admit a FAILED DECOMPRESSION.

[An Overview of Pathological Comorbidities]

[Read More]

[Read More]

[Read More]

[Discussed in the CCI Article]

[Discussed in the CCI Article]

References:

1 “Encyclopedia of the Human Brain | ScienceDirect.” Sciencedirect.com, 2019,www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780122272103/encyclopedia-of-the-human-brain.

2 "Overview: Chiari Comorbidities & Etiological/Pathological Cofactors [Revised]" | ChiariBridges.org, 2019,

https://chiaribridges.org/overview-chiari-comorbidities-etiological-pathological-cofactors/.

3 "Dimensions of the Posterior Fossa in Patients Symptomatic for Chiari I Malformation but without Cerebellar Tonsillar Descent" | BioMed Central, 2005, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1343586/.

4 "Mechanisms of Cerebellar Tonsil Herniation in Patients with Chiari Malformations as Guide to Clinical Management" | Acta Neurochirurgica, Springer Vienna, 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2887504/.

5 "Neurological and Spinal Manifestations of the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes" | American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 2017, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajmg.c.31549/.